Sustainability Research Papers

December - 2024

The Long-Term Target for International Public Climate Finance – The Landscape After the Decision at COP29

The 29th Conference of the Parties (COP29) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), dubbed the ‘Finance COP’, carried the weighty responsibility of defining a new climate finance goal— the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) to respond to the urgency and scale of the climate crisis while aligning with the broader objectives of the Paris Agreement.

November - 2024

Commitments to the Energy Transition – Leaders and Laggards

Between 2014 and 2023, the Earth was already 1.2°C warmer than pre-industrial levels (1850–1900). In 2022, carbon-intensive energy sources (coal (33%), oil (24%), and natural gas (16%)) accounted for 73% of global GHG emissions, which continue to rise. Reversing global warming requires an overhaul of the energy system. The “energy transition” involves shifting from fossil fuels to renewable energy to reduce emissions, lower costs, and address geopolitical concerns, though fossil fuel subsidies distort markets. What countries are leading the energy transition? What differentiates climate action leaders and climate laggards? What can laggards learn from leaders on achieving a just energy transition?

October - 2024

Key Priorities for COP29: What Can We Expect From This Year’s Climate Conference?

Summer 2024 recorded the hottest temperatures ever, making it increasingly likely that this year will again break global temperature records. Such developments

underscore the urgent need for decisive global action. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) process, particularly through its Conferences of the Parties (COPs), provides a critical platform for fostering international cooperation on climate policy. These gatherings help shape a global roadmap for sustainable development and the realization of the long-term targets of the Paris Agreement (PA). This year, COP29, to be held in Baku, Azerbaijan, is expected to play a pivotal role in addressing the key issue of scaling up international climate finance to enhance mitigation and adaptation strategies to curb further warming What is the NCQG and why is it set to dominate discussions at COP29? Can COP29 deliver on the final operationalization of carbon markets under Article 6?

September - 2024

Marine Carbon Dioxide Removals (mCDR) – Emerging Technologies and Regulation at Various Levels

Alongside substantial and rapid emissions reductions, Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR) is necessary to keep global warming to well below the 2°C temperature goal set by the Paris Agreement. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the global community have emphasised the importance of CDR to reduce atmospheric CO2 and manage potential overshoot scenarios. While the attention has so far predominantly focused on land-based CDR methods, marine CDR (mCDR) approaches have increasingly moved into the spotlight. What significant challenges does the implementation of mCDR methods face? How can dedicated political solutions help address the challenges associated with mCDR? What are the strengths and limitations of the most prominent mCDR approaches?

August - 2024

Opportunities and Challenges for Doubling Energy Efficiency Rates by 2030 as Agreed at COP28

Energy efficiency relates to the level of energy consumed for a given output. On a macro-economic level, energy intensity is

used as a proxy for energy efficiency, which is related to the overall economic output, such as the GDP1. Since the adoption of the Paris Agreement, there hasn’t been a shift in terms of global evolution of energy intensity. COVID-19 and the energy crisis set on by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, climaxed the energy efficiency rate globally to 2%, however, this value tumbled to 1.3% again in 20232. With the GDP dependent on fossil fuel export for the main hydrocarbon exporting countries, the related fossil fuel subsidies do not give an incentive to energy efficiency measures. What is energy efficiency? What is the status quo on energy efficiency globally? What are the challenges and opportunities in the MENA region?

July - 2024

Nature-Based Solutions: Mitigating Climate Change Within the UNFCCC Context

In 2023, the sixth United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA) convention provided the first multilateral definition of Nature-based Solutions (NbS), emphasizing their dual role in protecting nature and benefiting humans and biodiversity. Although not explicitly recognised under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) framework, NbS are acknowledged through references to, inter alia, ecosystems, forests and carbon sinks in the Paris Agreement and CoP Decisions. Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) submissions have increasingly mentioned (indirectly and explicitly) NbS, especially in the second round. What are Nature-based Solutions? What is the role of NbS in the context of the UNFCCC, particularly in climate change mitigation? Does the private sector have a role in financing NbS activities?batteries, metal-air batteries and redox flow batteries.

June - 2024

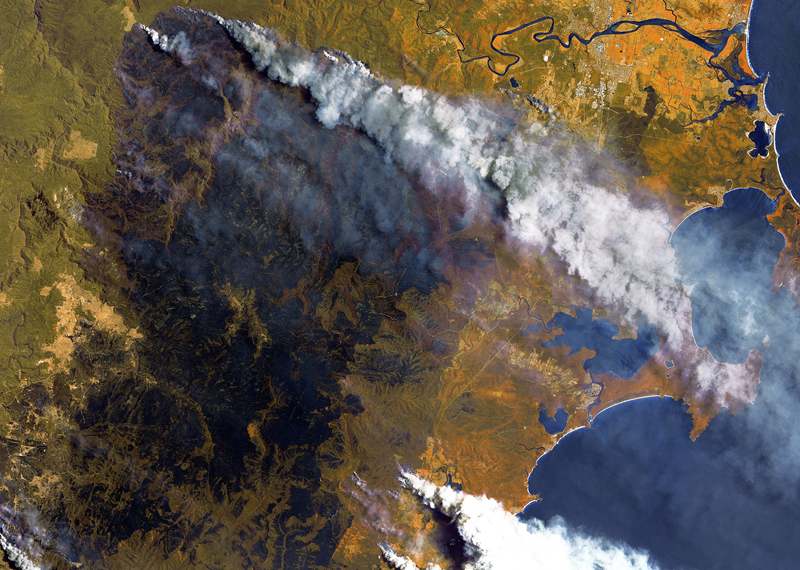

Unravelling the Implications of Climate Change for Energy, Food, and Water Security

Global climate change is becoming more severe, as evidenced by the global mean temperature reaching a record high of 1.45 ± 0.12 °C above the pre-industrial levels in 2023.01 Ocean temperatures and sea levels are also at record highs: average global sea surface temperature for February 2024 over 60°S–60°N was 21.06°C, the highest record for any month in the dataset.01 At the same time, Antarctic sea ice and glaciers are reaching record lows.02 These changes in climatic parameters are causing long-term shifts in weather patterns and more frequent extreme weather events. As a result, critical resources such as water availability as well as energy production and food security are being affected.01 This paper examines the impacts of climate change on energy, food, and water security, and explores potential solutions to reduce vulnerability and improve resilience.

May - 2024

Accelerating Renewable Energy Investments to Meet COP28 Goals by 2030

At COP28, over 130 countries committed to tripling global installed renewable energy (RE) capacity from around 3,400 gigawatts (GW) in 2022 to 11,000 GW in 2030 or 60% of global power generation capacity.1,2 Thus, more than 1,000 GW of new installed RE capacity will have to be added on average every year.3 In 2023, a 50% growth of new RE – the biggest in the last 20 years – added 510 GW, spearheaded by China.4 This capacity addition was possible thanks to more than USD 660 billion in RE investments, twice as high as in 2015 when the Paris Agreement was signed.5 However, to achieve the 2030 target, around USD 1.3-1.55 trillion will need to be invested annually,6,7 30% of which is expected to come from the public sector alone.8 What are the barriers to further RE investment? How will the public and private sectors scale up such investments? What factors could accelerate RE investments to achieve COP28 targets?

April - 2024

Direct Air Capture, Mineralisation and Storage of CO2 – Opportunities for the MENA Region

As the world grapples with the consequences of anthropogenic emissions, the Middle East, and North Africa (MENA) region stands at a critical juncture. Renowned for its vast energy resources and burgeoning industrial sectors, the MENA region is both a significant contributor to global carbon emissions and a pivotal player in the transition towards sustainable development. Against this backdrop, exploring the potential of Direct Air Capture (DAC) and carbon dioxide (CO2) mineralisation within the MENA region may offer opportunities for innovation, economic diversification, and environmental stewardship. What is Direct Air Capture (DAC) and carbon dioxide (CO2) mineralisation? How can they be utilised in the fight against global climate change? Why are such processes gaining significance?

March - 2024

The Pros and Cons of Biodiversity Crediting

A significant financial gap exists between the resources currently allocated to biodiversity conservation and the funding required to achieve the framework’s ambitious objectives. Traditional sources of funding fall short of meeting the scale of investment needed to address the biodiversity crisis effectively. In response to this funding short-fall, there has been growing interest in exploring innovative financing mechanisms, such as biodiversity crediting. Biodiversity credits represent a novel approach to mobilising private sector investment for conservation efforts, offering a potential solution to bridge the financial gap and accelerate progress towards achieving the goals outlined in the 2022 Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF). What are the pros and cons of biodiversity crediting in general? What are recommendations on how identified drawbacks can be mitigated?

February - 2024

Race to Climate Resilience: Front-Runners and Laggards in Advancing on Adaptation

Anthropogenic climate change is one of the most pressing global societal challenges and has a profound global impact worldwide. The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries present an intriguing case study due to their unique combination of high-income status and high vulnerability to climate change. As high-income economies recognised by the World Bank with a combined GDP surpassing USD 3.5 trillion, and status as leading oil producers and exporters, these nations offer a distinctive perspective on managing climate change impacts in affluent regions. Whichcountries in the region are frontrunners in adaptation efforts? Which countries have built upon existing national adaptation plans and undertaken activities funded by the Adaptation Fund (AF) and the Green Climate Fund (GCF)? Which countries are falling behind and require further engagement to tackle their climatechange vulnerability challenges effectively?

January - 2024

Key Challenges in Financing Responses to Loss and Damage as Climate Change Impacts Escalate

The 28th Conference of Parties (COP28) was a landmark event for loss and damage (L&D) negotiations, as the L&D Fund was successfully operationalised on the first day of COP28 and received initial contributions of over USD 0.7 billion. However, despite this achievement, the future of L&D finance remains uncertain in this critical year for climate finance when countries will agree on a new collective climate finance goal (NCQG) from 2025 onward to supersede the – not yet reached – USD 100 billion target.

The paper aims to shed light on three key aspects: 1) the need for clear definitions to support financing of L&D responses 2) the key developments and agreements leading up to the establishment and operationalisation of the L&D Fund and 3) crucial aspects that still need to be addressed in operationalising the

L&D Fund.

December - 2023

COP28 Unpacked: Assessing Outcomes and Shaping the Climate Policy Agenda

As a key event in the global climate calendar, the 28th Conference of the Parties (COP28) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), hosted by the United Arab Emirates (UAE) in Dubai, was tasked with conducting the first official assessment of the world’s progress under the Paris Agreement (PA) and identifying remaining challenges. The conference was able to conclude this “Global Stocktake” (GST) and notably, also set up the previously highly contested Loss and Damage (L&D) Fund on its first day. However, despite these significant achievements, the overall success of COP28 was mixed given that several negotiation topics either did not achieve outcomes at all or the results were perceived as weak and unsatisfactory. This paper, on the outcomes of COP28, builds on the analysis presented in the Al-Attiyah Foundation’s November paper,1 which provided a detailed background on COP28 with a focus on the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region.

November - 2023

What Will the Second UNFCCC COP in the Gulf Region Deliver?

Since 1995, the Conferences of the Parties of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC COPs) have provided a vital platform for addressing the manifold challenges posed by anthropogenic climate change. Over the years, COPs have evolved from small gatherings of government negotiators to bring together tens of thousands of people from the global community working to address climate change. Besides strengthening global cooperation on all levels, COPs showcase innovative solutions. This year’s 28th COP (COP 28) held in Dubai, UAE is the second COP hosted in the Gulf region after COP18 in Doha, Qatar in 2012. What significant outcomes are likely to emerge from COP28? What impact can COP28 have on the race to net-zero carbon emissions by midcentury? What can we expect from the first Global Stocktake (GST) at a COP? Will COP28 serve as a catalyst for further climate action in the Middle East?

October - 2023

The Importance of Regional Cooperation for Climate Change Adaptation and Building Resilience

The global community stands at a pivotal juncture in its fight against climate change. As the impacts of climate change become increasingly evident, the need for collective action and regional cooperation in addressing its impacts gains prominence. Climate change’s impacts cut across all sectors and levels of governance, underscoring the necessity for regional cooperation through multi-stakeholder partnerships. How will climate change affect the MENA (Middle East and North Africa) region in the coming decades? To what extent do MENA countries collaborate regionally to combat climate change? What are some key adaptation strategies to shield populations and economies from the impacts of global warming?

September - 2023

Strategic Approach to the Implementation of Article 6 of the Paris Agreement in the MENA Region

Since the adoption of the ‘rulebook’ for international carbon markets and nonmarke approaches under Article 6 in 2021, many countries have moved towards the implementation of international market-based cooperation. This can serve different objectives, including meeting and enhancing NDC targets, attracting investment for high-cost mitigation actions, facilitating technology transfer, and building capacities. Countries that want to benefit from market-based cooperation under Article 6 – sellers and buyers alike – need to become Article 6-ready. Who are the frontrunners in the MENA region with regards to climate transition policy? Will additional resources need to be deployed within the region to unlock the full potential of international carbon markets and non-market approaches?

August - 2023

Compliance and Voluntary Carbon Markets – What Are the Fault Lines?

A carbon credit is a tradable unit that represents one metric tonne of real, additional, and permanent greenhouse gas emission reductions or removals issued by a carbon crediting programme and recorded in a carbon registry. Compliance and voluntary carbon credit markets can accelerate global climate efforts by mobilising finance for additional and ambitious climate action. Ensuring the integrity of carbon credits and their use is the key to unlocking the potential of these markets. What is the role of carbon credits in global climate efforts and how can they be used voluntarily and for compliance? What are the key fault lines or concerns relating to the integrity of carbon credits, their use, and related claims, and how can they be addressed?

July - 2023

The Role of Natural Gas – Transition Fuel or Part of the Long-Term Global Energy Mix?

Natural gas has seen a rapid expansion since the 1970s as it has many attractive characteristics, including a low direct greenhouse gas emissions intensity. Many analysts have therefore seen it as a key “bridge fuel” to cushion the energy transition from coal and oil to renewables over the next decades. However, an increasing understanding that methane emissions in gas production and transportation are generally high, as well as the sudden realisation of the vulnerability of natural gas importers, as highlighted by the Russian invasion in Ukraine, has recently dimmed the prospect of natural gas.

June - 2023

Energy Efficiency in High-Rise Buildings in Desert Climates

The Gulf region has witnessed a significant increase in its number of skyscrapers over the past few decades. This trend of high-rise buildings in the Middle East can be mainly divided into two distinct phases. The first phase, from 1990 to 2000, was marked by the dominance of oil exploration and profits, which prioritised economic growth over energy efficiency. While the second phase was characterised by a shift towards sustainable design and greater awareness towards energy efficiency and financial savings associated with it.

May - 2023

Green Hydrogen Opportunities for the Gulf Region

Green hydrogen can help decarbonise hard-to-abate sectors like refinery, steel and heavy duty transport and the chemical industry. The Gulf region is well positioned to establish itself as a hydrogen hub as it has cheap and abundant renewable energy resources and is located in the vicinity of major hydrogen consumption centres like Europe and Asia. What risks does a massive uptake of green hydrogen pose to the region? What is green hydrogen and what is its current and future contribution to a sustainable global development? Which hydrogen policy frameworks are currently existing in the Gulf region?

April - 2023

Renewable Energy Investments in Times of Geopolitical Crisis

Since the beginning of the 21st century, renewable energy (RE) for power generation has experienced remarkable global growth and development. By the end of 2022, global RE generation capacity amounted to 3,372 gigawatts (GW), growing the renewable power generation capacity by a record 295 GW or by almost 10% compared to 2021. However, disrupted supply chains, spiking interest rates, and an increase of input costs stemming from COVID-19 pandemic and the

Russian invasion of Ukraine have reduced the attractiveness of RE investments.

March - 2023

The Implications of Cross-Border Carbon Taxes on Geopolitics and International Trade

Climate change mitigation through greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction or removal from the atmosphere is a global public good that requires significant investments by governments and businesses. Although benefits accrue to all humans, the problem of free-riding arises from such practices. How can the freeriding problem related to climate change mitigation action be resolved? What role do cross-border carbon taxes play in the climate change policy landscape? Who are the front-runners in terms of implementing cross-border carbon taxes and how will they influence shifts in trading flows?

February - 2023

Agri-Pv: Harvesting Agriculture and Solar Energy for a Sustainable Future

Several challenges prevent the widespread uptake of Agrivoltaics (Agri-PV) including existing farming practices, high initial investment costs due to low market penetration and awareness, lack of government incentives and limited technical knowledge of best practices for adoption. How can Agri-PV benefit the MENA region by strengthening the energy transition while reducing GHG emissions? How can Agri-PV address multiple crises such as arable land scarcity and resulting food insecurity? These are some of the questions addressed in this research paper.

January - 2023

The Impact of High Interest Rates on Sustainable Investments

Sustainable investments are investments that seek to achieve a financial return while also generating positive effects on society, the environment, and the economy. Given the amplified focus on decarbonisation and green economy, sustainable investments are becoming increasingly attractive and are crucial to enable the low-carbon transition.

How sensitive are sustainable investments to interest rate changes compared to non-sustainable investments? What role did low interest rates play in the growth of sustainable investments in the past decade?

December - 2022

COP27: Taking Stock

Negotiations at COP27 revolved around the remaining prospects of avoiding a global temperature increase of 1.5°C; the provision of climate finance to assist developing countries to mitigate and adapt; and the establishment of new funding to compensate vulnerable countries for loss and damage.

Carbon markets also saw action, with decisions on Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes (ITMOs) and the establishment of a new carbon credit: a Mitigation Contribution Emission Reduction (MCER). What will be the overall impacts of these COP27 outcomes? What further key agenda items have emerged, and what work remains in the run-up to COP28?

November - 2022

The Just Transition To A World Powered By Sustainable Energy

The energy transition will affect fossilfuel dependent countries, communities, and localities very differently. The financial flows from developed countries to developing countries have always been a thorny issue in climate change negotiations. What is the Just Transition approach to climate mitigation? What are the various mechanisms and instruments to ensure equitable responsibility for the emitters and the climate-vulnerable? Can a Just Transition be achieved by 2050?

October - 2022

Technology and Climate Change

There is general recognition that technological breakthroughs will play a key role in climate change mitigation and adaptation. New technologies are required to expand the scope of low-carbon energy, facilitate atmospheric carbon removal, tackle hard-to-abate sectors, and deal with the unavoidable impacts.

What are some of the promising technologies in the medium to long-term? What policy instruments are needed to fast track the development of necessary technologies for combating climate change?

September - 2022

Mind the Gap: Enhancing NDCs before COP27

Under the Paris Agreement process, countries are required to submit new or updated nationally determined contributions (NDCs) at least every five years, and successive NDCs should represent progression and a higher level of ambition. The first round of new or updated NDCs was due in 2020.

What enhancements are being made to NDCs in the run-up to COP27 in Egypt? How do these revised NDCs compare with the initial NDCs? How significant are scaling up of ambitions by the major greenhouse gas emitters? How does this first round of revisions meet the scale of ratcheting up of ambitions required in future NDCs to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement?

August - 2022

The Role of the Middle East in Global Climate Diplomacy

The Middle East is playing a growing role in international climate diplomacy through giant clean energy investments on its own soil, and also in emerging regions (particularly Africa). It is achieving these through combined efforts of ministries, sovereign wealth fund (SWFs) and national energy companies. However, the various Middle East countries exhibit different interests, levels of engagement and strategies. What do their efforts mean for future climate ambition? What are their approaches to climate diplomacy, and where is it helping or hindering global progress?

July - 2022

Drying Up: Climate Change & Water Scarcity

Climate change will alter patterns of precipitation, river flow and evaporation. At the same time, water use is ncreasing in many countries. This brings increasing challenges of providing sufficient, affordable, high-quality water for agriculture, human needs, and industry, while not depriving ecosystems. How will water scarcity manifest itself? Which regions and areas of human activity are most threatened? How can the challenges be addressed?

June - 2022

Affordable & Clean Energy for All: The Energy Mix under SDG7

Sustainable Development Goal 7 (SDG7), which is among the 17 UN SDGs established in 2015, aims to “ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all by 2030.” Despite reasonable progress between 2015 and 2020, advances seem to have stalled, creating concerns that success by 2030 is out of reach. How will SDG7 impact the energy mix of the future? What sources of energy will ensure sustainability and availability of supply? What is the progress so far on energy access, energy efficiency and renewable energy? How have advances on SDG7 been affected by the Covid-19 pandemic and Russia’s war against Ukraine? Where do fossil fuels stand with regards to SDG7?

May - 2022

Invisible Menace: What Will it Take to Implement the Global Methane Pledge?

At the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference, more commonly referred to as COP26, over 113 countries signed the Global Methane Pledge to reduce their emissions 30% by 2030. Tackling methane emissions, which is responsible for onethird of current global warming, is one of the most effective short-term measures that can be taken to address climate change. What policies are planned to be employed? What are potential risks? What does this mean for the future of natural gas?

April - 2022

The 2030 SDGs Voluntary National Reviews: Are They Enough?

The 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) agenda provides for regular Voluntary National Reviews (VNRs) to assess progress on achieving the SDGs.These have been conducted since 2016, with a growing number of countries participating.

How does the VNR process work? What are the findings of the VNRs so far? How could the process be strengthened? And what can be learnt from the VNRs for other international cooperation?

March - 2022

The Role of the World’s Forests in the Fight Against Climate Change

Deforestation accounts for 15% - 20% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, while regrowth is an essential carbon sink. Forests store about 660 gigatonnes (Gt) of carbon, equivalent to almost 80 years of global emissions. They are also an essential store of biodiversity, a home for many peoples and a crucial part of the hydrological cycle.

What is the environmental role of forests? What are the drivers of deforestation? And what policies are being implemented at the national and international level?

February - 2022

Carbon Markets after COP26:A Price on Carbon

The Paris Agreement’s Article 6, on carbon markets, was a crucial part of the COP26 negotiations. A price on carbon is a key tool for reducing global emissions in an efficient and fair way. But there were serious challenges in reaching a workable text, that would allow carbon markets to function effectively while avoiding doublecounting or encouraging unsustainable activities. What was concluded and what remains to be agreed? Where do global carbon and offset markets now stand? How will Article 6 of the Paris Agreement further accelerate the development of a global carbon market?

January - 2022

Policy & Politics: The EU’s Green Taxonomy

The European Union’s draft green taxonomy of sustainable investments was released in December 2021. The document is intended to outline which types of projects and technology can be claimed as ‘sustainable’ by companies, to avoid allegations of ‘greenwashing’. It can also affect which investments are eligible for certain types of EU funding. Yet the political compromises to reach agreement have led to accusations that the taxonomy unfairly penalises certain technologies. What is the significance of Green Taxonomy? Where are the areas of unclarity and controversy? How has the European Commission attempted to balance sciencerelated policy and the differing political stances of the member states, in areas such as nuclear, gas and biomass?

December - 2021

COP26: Outcomes & the Road Ahead

COP26 marked the transition of the historic Paris Agreement from rulemaking to implementation. Significant outcomes were achieved during the delayed event, from agreeing to stronger 2030 emissions reduction targets, concluding the rulebook for Article 6, scale-up of finance to least developed countries (LDCs), collective commitments to curb methane emissions, reverse forest loss, accelerate the phase-down of coal, and end international financing for fossil fuels.

However, financial support for adaptation and loss and damage saw lesser action. What will be the impact of COP26? Will new commitments be enough to keep the 1.5°C target achievable? What work remains in the run-up to COP27 and COP28? And what do the outcomes mean for future oil and gas production?

November - 2021

The Progress of Green New Deals in Europe and the US

Governments in Europe and the USA want the recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic to be the springboard for environmentally and socially progressive policies. The EU has proposed the ‘European Green Deal’ and ‘Fit for 55’, while the administration of President Biden has put forward a ‘Green New Deal’ and the strategy of ‘Build Back Better’.

What are key factors and differences between the two continents’ green deals, and how do these compare to eco-environmental policies in other countries? What are the challenges and chances of success on the environmental and economic aspects?

October - 2021

Net-Zero Scenarios: What Will the Energy Landscape Look Like?

An increasing number of countries have committed to reach net-zero carbon emissions, usually between 2050-70. Any remaining emissions of carbon dioxide or other greenhouse gases would be cancelled out by increased forestry or other methods to remove atmospheric CO2.

What are realistic scenarios for reaching net-zero by mid-century? What are the key features of each? What are the conditions for them to be realised, and what are the environmental, technological, economic and political implications?

September - 2021

New Frontiers: Emerging Sustainable Technologies Of The Next Decade

New technologies are emerging that improve sustainability – some in response to climate concerns, others as a result of unrelated lines of research or consumer trends.

Energy technologies are particularly important of course, from advanced solar cells and high-capacity batteries to hydrogen and nuclear fusion. Artificial intelligence and automation bring a wealth of possibilities, particularly for improved energy efficiency. Other novel sustainable systems cover remote sensing, food supply and transport.

August - 2021

Climate Change And Food Security

Climate change is leading to overall warmer climates, as well as to less predictable weather, more extreme events, and shifts in precipitation. At a national and global level, farmers and governments must plan to produce more food with lower environmental impact in a more challenging climate.

How does climate change affect food security? What impacts are being seen today and predicted in future? What adaptation options are available to mitigate climate-related food insecurity, and how are they being deployed?

July - 2021

Climate Change Science

Climate change science has advanced and evolved enormously over the past few decades, data collection and modelling are much more sophisticated, and new questions are being explored by scientists and governments alike.

This paper looks into, what are the key features of our evolving understanding of climate change science, in terms of the pace, effects, regional distribution and attribution of extreme events? And, what are the most important remaining uncertainties?

June - 2021

Critical Materials For Energy Transition

The emerging new global energy system requires new materials that were not traditionally in high demand. Their currently known reserves are often small, technically difficult to obtain, or concentrated in politically challenging countries. Governments and companies are paying growing attention to ensuring that the clean energy transition can access sufficient quantities of such materials at reasonable prices.

What are the key materials for energy transition? What critical components are required for solar, wind, battery and other new energy systems? How will supply and demand of each evolve, and where are they located? What can be done to substitute, recycle or reduce the use of each? What are the geopolitical implications associated with the availability of such materials?

May - 2021

Strategies for Sustainable Production and Consumption of Natural Resources

Natural resources encompass a wide range of physical and biological materials, entities and systems, from coal or iron ore, to a freshwater lake, North Atlantic cod, the Amazon rainforest, sunlight or the atmosphere. Some of these are exhaustible, some regenerate but can be damaged or depleted, and some are renewable and non-depletable. During the industrial era, and even more so in the era of human-made climate change, attention has been drawn to the multiple threats of unsustainable resource use.

What are the key natural resources in danger of overconsumption or depletion? What are the potential consequences of a diminishing state of the world natural resources? What is being done and can be done to reduce, reuse, recycle and replenish natural resources?

April - 2021

Sustainable Development Roadmap from the 75th United Nations General Assembly

The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Roadmap is the blueprint for fighting poverty and hunger, confronting the climate crisis, achieving gender equality, and much more, within the next ten years, the Decade of Action. How realistic is this roadmap to be achieved, and what areas still require work to be done? During a period of uncertainty, will the roadmap show the way forward to a sustainable future postcoronavirus?

March - 2021

Net-Zero Carbon Economy By 2050

A growing number of countries are committing to ambitious target of net-zero emissions by 2050, as a show of commitment to implement the Paris Agreement. Sectoral net zero roadmaps are also beginning to emerge. For example, the International Energy Agency (IEA) is due to publish, in May this year, it’s first comprehensive roadmap for the entire global energy sector to reach net-zero emissions by 2050.

Is a net-zero carbon economy a realistic proposition or a pipe dream? What commitments have been made so far, and what needs to be done to make them reality?

February - 2021

Greening The LNG Industry

As countries continue to ramp up their climate change ambitions, the role of natural gas will be enhanced, as burning natural gas produces less greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) than burning coal and crude oil. However, companies producing, processing and transporting gas need to ensure that methane leaks are kept to a minimum, in order for gas to be widely accepted as more climate friendly than coal. Why are GHG emissions a growing concern for LNG exporters and buyers? How does the carbon footprint of LNG production and transport differ between projects, and what are the underlying drivers? How does the carbon footprint of LNG compare to pipeline natural gas and to other fossil fuels? What can companies do to reduce the carbon footprint of brownfield and greenfield LNG? Can this become a competitive differentiator?

January - 2021

Carbon Neutrality & The 75th UN General Assembly

World leaders, captains of industry and civil society organisations, see the Paris Agreement as the last hope for humanity to address the impact of climate change and preserve foundations for a healthy planet. Consequently, many state and non-state actors are signaling their intentions to ramp up climate change action, with announcements of ambitious net-zero roadmaps, at or immediately after the 75th UN General Assembly. What were the critical decisions and noteworthy announcements? How achievable are the targets on carbon neutrality, and how do they relate to the Paris Agreement’s goal? What are the implications of these targets for the energy sector? How does the way forward relate to other key global challenges considered by the UNGA?

December - 2020

Nationalism - A Threat to Global Environmental Diplomacy & Policy?

Globalisation, the process of increasing globalism of trade, information, migration, and culture, has been recently under pressure from renewed nationalism.Populist nationalist leaders in countries such as the US, UK, and Brazil have challenged international agreements and often threatened to withdraw from climate and environmental action. How is international geopolitics impacting sustainable economic development, effective environmental legislation, transboundary trade in goods and services, access to sustainable energy, and the fight against climate change? What shifts in the US policies of the past four years, should the world expect from the new incoming administration? What are the challenges and opportunities for industry in general, and particularly the energy industry?

November - 2020

Growing Climate Change Activism

Environmental activism, in general, and focus on climate change, in particular, has witnessed a shift from traditional street movements to political, institutional, corporate, and online forms, facing the energy industry with bottom-up, top-down, and internal pressures. How has climate change activism succeeded in changing the energy landscape, attitudes and perceptions of investors, and expectations from shareholders? How is climate change activism adapting to new challenges and taking up novel tools? What role is climate change activism playing globally and in what way is this likely to shape the energy and climate change policies of the new US administration?

October - 2020

Plain Sailing And Soaring Smoothly: Emissions Reduction Strategies In Shipping And Aviation

The Paris Agreement has generated momentum to reduce greenhouse gases (GHG) emissions within national borders. However, international transport is also responding to the imperative to cut its carbon footprint. The International Maritime Organisation

(IMO) and International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO) have both set policies to align their industries with the Paris goals. While the two sectors are not significant emitters today, they are an essential part of future forecast growth. These two transport industries face a complex mix of options, including efficiency, mode shifts, and alternative propulsion, with varying technological and commercial readiness. But, a broad set of actors across the value chain have to be aligned to deliver low-carbon options with the right timing, performance, and costs.

September - 2020

Carbon Disclosure and Carbon Neutral Certification

As an increasing number of companies declare plans to reach “carbon neutrality” within the foreseeable near future, carbon disclosure has become an ever more prominent topic. It is the practice of assessing and reporting a company’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, its impact on climate, its strategic and risk management processes on climate, the impact on its business, and its plans and targets for improvement.

However, inconsistencies remain, particularly the different treatment of emissions throughout a company’s supply chain and that of its customers. Improving standardisation and public disclosure will likely be required by regulators along with standard financial data, and will make it essential for all major companies, even non-listed ones, to comply.

August - 2020

Are We Doing Enough? Global Action on Climate Change

The signatories of the 2015 Paris Agreement submitted ‘nationally determined contributions’ (NDCs), their individual and voluntary planned actions to reduce emissions and otherwise tackle climate change, with the intention to achieve the Paris aspiration of limiting warming to no more than 1.5°c by 2100. Five years after the Agreement, the deadline is approaching to review and update the NDCs.

How does the review process work? How ambitious and achievable are the existing NDCs, and how are they likely to be upgraded? What would the impact of existing and new NDCs be on energy production and demand? And what will the current round of NDC updates bring in the process of climate diplomacy?

July - 2020

Corporate Social Responsibility in the Energy Sector

As the concept and range of CSR continuously expand, new trends emerge to meet such concerns. These trends are reflected in the energy sector through attention to green energy investment and reduced contribution to climate change; community engagement on major new projects; bridging the talent gap to produce highly-skilled new employment; and working with governments to introduce social responsibility policy reforms. Nevertheless, there are several challenges for CSR programmes in the energy sector which, in turn, are likely to be exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic and associated recession.

June - 2020

Waste Management in the Oil & Gas Industry

Managing waste from oil and gas operations is a topic of growing importance, with emerging strategies and innovative approaches to limit both waste and its impact, as it poses a significant cost to operations, and in many cases, a loss of potential revenues.

This report looks into how the industry can engage proactively and constructively, through various existing coalitions and industry associations, with government, environmental groups, and civil society. And further, how it can employ new technologies to improve the ability to monitor, reduce and dispose of waste appropriately.

May - 2020

Climate Adaptation: Risks and Measures

As climate change is projected to worsen further in coming decades, even with strong mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions, adaptation measures are essential to limit threats to peoples’ wellbeing, livelihood, water, food, infrastructure, energy security and economic growth. Many climate-exposed countries have consistently emphasised adaptation as a critical consideration in their climate change strategy. Each city, country and region has to answer the questions: what is the expected real impact of all the major effects of climate change on health, life, and various aspects of the economy? And what measures can be taken to adapt and improve resilience?

April - 2020

Carbon Capture and Storage: What is its role in climate mitigation?

The Paris Agreement on climate action, and the IPCC report on the impacts of warming of 1.5°C above preindustrial levels, emphasise the importance of a range of different low carbon approaches in limiting dangerous climate change. What is the role of carbon capture and storage (CCS) in major studies of climate mitigation options? What is the global status of research, development and deployment of CCS technologies? How economically viable are CCS technologies? How far are we from enabling cost competitive deployment of CCS technologies in coal-fired power plants? What is the potential to further develop CCS technologies for their subsequent widespread use in all carbon-intensive industrial sectors?

March - 2020

Renewable Energy Policies: Work in Progress

Policies to encourage renewable energy have increased steadily since the late 1990s, and particularly after the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change.

These have reduced the cost of renewables, encouraging widespread adoption. Which policies are countries adopting to boost the competitiveness and deployment of renewable energy? What drives them to do so? What are the evolving trends in new or reshaped policy? And what can fossil fuel exporters do in the field of renewable policy?

February - 2020

Carbon pricing: Lessons for the Middle East

Attention has returned to carbon pricing as a marketbased method for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Cap-and-trade and carbon taxation are the two contrasting methods, with an increasing number of jurisdictions adopting one or other or a hybrid.

What are the advantages and disadvantages of these two methods? What are the implications for the Middle East as key markets for its exports adopt carbon pricing? And what issues should Middle Eastern countries tackle if they were to adopt a carbon pricing framework themselves?

January - 2020

Green LNG – Opportunities and Challenges

As gas is the fastest-growing fossil fuel, so Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) is one of the fastest-growing methods of delivering gas to international markets. LNG has the potential to cut greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and other pollutants in coal-heavy regions such as east and south Asia.

However, gas and LNG are also coming under environmental pressure because of associated methane and carbon dioxide emissions. What options exist to reduce LNG’s GHG footprint? How do different projects compare? And what other approaches are open to LNG exporters to strengthen their claims that LNG provides a sustainable energy solution?

December - 2019

Sustainable Energy: 2020 and Beyond

The year 2020 is set to be a pivotal introduction to a key decade in sustainable energy. Political decisions on progressing the Paris Agreement to reduce GHG Emissions, and the US election, will set the course for climate change regime for most of the first half of the 2020s. Ambition on both climate and sustainable energy so far has been notable but insufficient, while implementation has been patchy and lagging. Key regional blocs are advancing at dramatically different speeds, and with widely varying domestic political drivers. Yet in Europe and the US in particular, bottom-up, local and corporate initiatives have gathered pace and may sweep national politics along. What signposts to the decade can be expected in 2020? Which key sustainable energy technologies will advance or lag behind?

May - 2019

Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs)

The end of 2018 marked two years since the ratification of the Paris Agreement, and two years from the first call for more ambitious pledges. The international community is cautiously observing collective efforts to reduce emissions. The Intern-governmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, concludes that staying well below two degrees is still within reach, but time is running out and successful emission reduction are a necessity in the coming decades.

April - 2019

Climate Change: How Risky to Qatar and the World?

In January of this year, the World Economic Forum (WEF) released its Global Risks Report 2019 on the major threats to the world economy. For the third year in a row, the report stated that environmental-related risks account for three of the top five global risks by likelihood, and four of the top five risks by economic impact, namely: “Failure of climate-change mitigation and adaptation,” “Extreme weather events,” “Water crises,” and “Natural disasters.”

February - 2019

Circular Economy: The Way to Grow a Sustainable Economy?

The term “Circular Economy” has become a byword for a good economic model for “Sustainable Development”. The concept has gained common acceptance and recognition as a more sustainable economic model and more desirable than the previous linear approach to economic planning. Whereas the philosophy behind a Circular Economy, developed in the 1960s, was ridiculed, with the evolution of sustainable development, it has since grown in acceptance and effectiveness for catalysing sustainable economic growth.

January - 2019

Green LNG: Is Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) the Clean Energy we need?

At the Paris Climate Accords, a common goal of curbing the temperature increase to below 2°C above the pre-industrial levels was agreed. All member nations agreed to commit resources to fight the rising global temperatures affecting our climate to safeguard the future of the planet. Logically, the advancements in renewable energy provide a path to revamp the energy sector and move away from non-renewable energy sources that are a major contributor to climate change. But, a complete shift presents economic challenges.